With the instability and uncertainty recently observed in the South African electrical grid, the phrase “off-grid” is being bandied and thrown around and has become a bit of a buzzword for those taking note of the energy state of affairs. In this context, the term going “off-grid” refers to a residential property cutting entirely its ties with their electrical supplier, opting to generate their own required energy through renewable sources and removing their dependence on municipal supply.

Next Renewable Generation’s experience with solar energy generation in the commercial and industrial space has led to several inquiries from homeowners regarding the viability, practical and financial, of solar installations on their own residential property.

What can you actually achieve with solar?

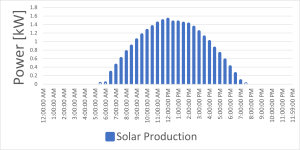

To determine whether solar is for you we need to understand the fundamental limitations solar PV has in a residential application. The most obvious limitation is that solar can only produce electricity during sunlight hours; as seen in the figure below which shows the trend of PV electricity generation during summer.

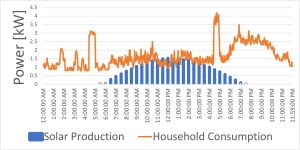

Compare that solar generation trend to the energy consumption trend of a typical South African home as seen below and there is a very clear mismatch. The mismatch means that no matter how many panels are installed, (even if rooftop space was unlimited), they will never fully cover a house’s consumption needs.

Compare that solar generation trend to the energy consumption trend of a typical South African home as seen below and there is a very clear mismatch. The mismatch means that no matter how many panels are installed, (even if rooftop space was unlimited), they will never fully cover a house’s consumption needs.

The figure also notes some typical reasons for the consumption profile, most notable being the times when an electrical geyser is turned on (around 4AM and again around 4PM). The maximum daily energy that a PV system could account for in this case is around 32%, adding more panels would simply result in energy being produced and wasted at times when it could not be used.

This brings us to the first philosophy or approach that can be adopted when considering a residential solar installation.

First philosophy:

Rather than considering going completely off-grid, it is possible to consider a grid-tied installation. This is when a property will receive electricity from both solar PV panels and from the Eskom grid. The amount of energy required by the house that can be covered by a solar energy system depends highly on the energy usage habits within the house.

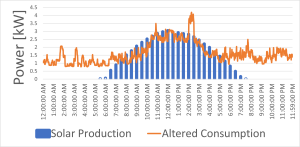

For example: if the house whose load profile is shown above instead had the geyser delayed to turning on in the middle of the day the solar and demand graphs look more like the figure below. Double the panel capacity to meet the shifted load allows a larger portion of the daily energy needs can be met, in this case around 65%.

This is achievable in homes where live in-tenants, domestic helpers or daytime energy users are present, or a home is occupied.

Second Philosophy:

Second Philosophy:

Excess energy produced during sunlight hours requires batteries to store the energy to be dispatched for use after the sun goes down. With a large enough battery and enough solar panels, it is possible to go completely off-grid (though as discussed in the next section the price is prohibitive). A smaller battery could be used to power only essential devices in the house, and though this often requires some DB rewiring it is probably the most practical solution for most people.

The cost of the technology

Quoting prices in this industry is a difficult task; every installation must be assessed case by case and only after an energy usage and needs analysis is concluded. Equipment and installation prices change with fluctuating exchange rates, different technology qualities, and the configuration of available rooftop space at a home. As such the pricing listed here are just a ballpark at the time of publishing this article and will fluctuate going forward.

Grid-Tied:

A medium ( ~3kWp ) solar system with only panels and an inverter will cost around R 70 000+. This will cover only a portion of your energy needs during the day, but it can cover more if your usage habits change to shift usage into the solar hours.

Grid-Tied with Batteries:

A solar PV system with added batteries that can supply essential loads will increase the cost to around R 150 000+. The essential loads such as lights, gate, alarm, and fridge will have power for about 12 hours with a system like this. The loads connected here will have a large impact on how long the battery charge actually lasts for and careful thought has to go into designing it as well as how it is operated during outage conditions.

Off Grid:

A final estimate is for going off grid. It cannot be stated enough how big a battery is needed (volume and footprint alone) to supply the energy needs of a full house without a change in usage habits. Between R 400 000 and R 500 000 will usually ensure that the house will be powered for a full day without sunlight.

Of course, the most important consideration for these solutions is the payback period. At the current cost of technology and energy solar panels alone will pay themselves off in several years, while a small battery system will only repay itself close to the end of the battery’s 10-year lifespan and an off-grid system will likely not repay itself. This means that while panels can be seen as an immediate investment; the return on a battery integrated system is going to be highly dependent on the price of battery technology in the future. The immediate benefit of including a battery system is the security of energy supply.

Conclusions

It need not be said, but you get what you pay for.

If the goal is battery backup or going strictly off-grid, then you must accept that there is a high price premium that comes with it. Truly off-grid systems need to be very carefully designed, sized, and managed.

The cost-effective option most often is to have a grid-tied system without batteries and understand that it will not account for all the household energy requirements but that a change in behavior will maximise the savings that can be realised.